How to Make Blue?

If you want to know what colors make blue, you may get two very different answers. The first one is simple: you can’t make blue because it’s one of the three so-called primaries. The second is a bit more complicated, but actually very interesting and much closer to the truth. So if you want to start an interesting conversation about art, graphic design or are just being curious, read on to find out how to make the color blue!

The Basic Color Wheel Explained

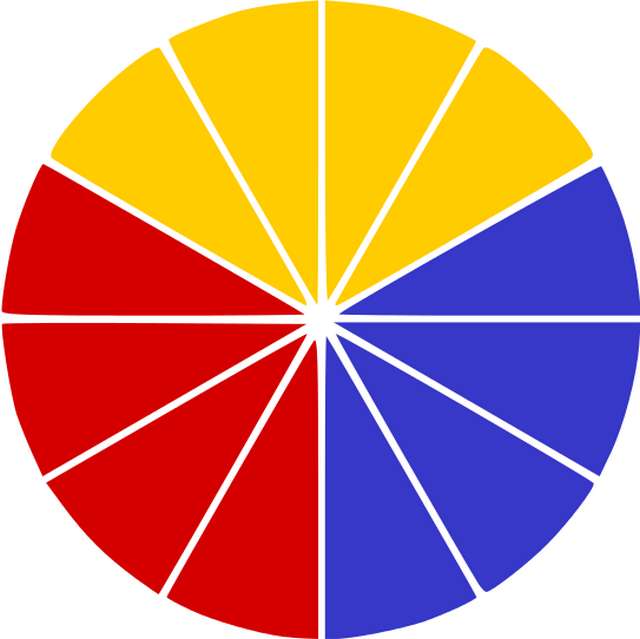

There are numerous theories about the color, but most of us are familiar with at least one – the color wheel, developed in 1666 by Sir Isaac Newton (he actually became a Sir almost 40 years after that). This theory explains all the colors by three basic, primary hues: red, blue and yellow. None of them can be made from other colors and every other hue you might imagine can be made by mixing two or all three primaries in right proportions.

This color wheel can be presented with a simple diagram, a color wheel of primary colors:

The so-called secondary color wheel or 6 color wheel looks like this:

Sometimes it is also called a complementary color wheel because the colors, lying on the opposites of the circle make complementaries to each other. As you already noticed, there are three other colors added – green as a mix of yellow and blue, orange as a mix of red and yellow, and violet (purple) as a mix of blue and red.

We can proceed with a tertiary color wheel, a color wheel with 12 colors:

Here we got six additional colors (blue-purple, blue-green, yellow-green, yellow-orange, red-orange, and red-purple) all being made by mixing one primary and one secondary color. It’s obvious we can go on and on with that, making more and more new colors. With an addition of white, gray and black we got different tints, tones, and shades as well, what leads us to next color wheel:

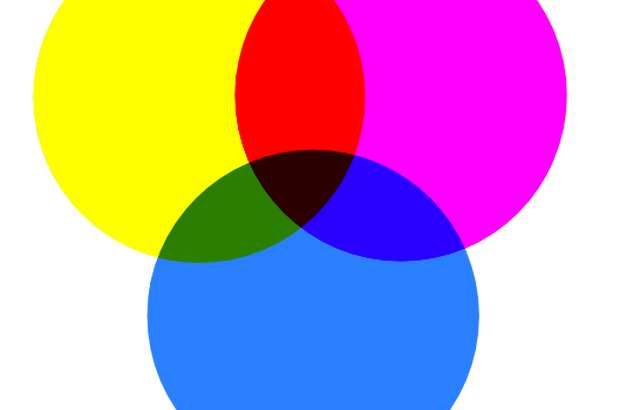

This kind of mixing colors is called additive color model, but in practice, we often use a subtractive color model as well. This one is based on a different, although still very logical premises. It starts with a white light, which is, as you probably already know, made of different colors. These can be individually seen thanks to the dispersion.

Each color has its own wavelength and each has different speed when passing the media (in the example above, it’s a glass prism). Instead of the white mixture, we are able to see its components and with appropriate filters, we can eliminate certain colors to see just one or more of them. The printing process at computer printing is based on this idea.

We start with a white sheet of paper and then apply series of filters, so only desired color(s) can be seen. Filters in common printing are called cyan, yellow and magenta. All of them are colors already but are used in mixtures to create hues that could be seen as the end result. You probably already heard of CMY abbreviation, called after first letters of these color filters, and we’ll get back to it later.

So What Two Colors Make Blue?

If we want to print blue color, we need two filters: cyan (it eliminates red) and magenta (it eliminates yellow). Similarly, other colors can be created:

To improve the quality of printing and reduce the costs another color was added into the CYM system – black, which could be otherwise created with an application of all three basic filters. This is how today’s most known printing standard CYMK was created. There are several theories what a K means, from being the last letter in black (B is already taken for blue – B in another system, called RGB) to the most believable K for Key, the color which is in most cases applied first for outlining.

But let’s get back to the color blue. Just like all other paints a blue paint is made from a pigment dissolved in a liquid vehicle (like water or oil). Typical paint made by classic procedures is a mixture of pigments (responsible for color), resins (keep pigments in place), solvent (to regulate the viscosity of paint) and additives (for fine tuning the properties of the paint).

Here how a blue pigment, called Fra Angelico, the starting point of so popular ultramarine blue color, is prepared:

This classic blue pigment is made from semi-precious stone Lapis Azuli and is the reason why blue color was for so many centuries reserved only for rich people. Today we have an enormous number of different pigments, some of natural, other of synthetic origin.

Do you need a list of blue pigments? Just read on!

Azurite

Cobalt Blue

Cornflower Blue

Egyptian Blue

Han Blue

Indigo

Manganese Blue

Maya Blue

Phthalocyanine Blue

Prussian Blue

Smalt (Saxon Blue)

Ultramarine (Lapis Lazuli)

Woad

Please note, some of these pigments contain toxic chemicals, especially heavy metals, so don’t play with them without prior knowledge and skills to handle them. This article is of informative nature only and if you want to know more about blue hues, you can simply check this list of different blue colors.

When we already have a pigment (or more pigments), the procedure goes as follows:

Please be aware of possible fumes, so take safety precautions. With this, we conclude our a bit longish answer to the seemingly simple, yet tricky question: »What makes blue?« See, colors are more of ideas than absolute facts, and each similar question can bring several right answers, all of the different logical concepts based on different perceptions.

This should not stop you from exploring the fascinated world of different colors. Have fun!